Lessons learned from a three-day lasagna

A deeply flawed cookbook reveals its writer's inexperience

Summer was slow to take hold in New York this year, and with the unseasonably cold winds of spring came the desire for lasagna.

While New York is now one of the least infected places in the country, on May 14th the pandemic was basically at its pinnacle and we were trapped at home with only our downstairs friends/neighbors in our quarantine pod. To help protect against COVID-19 we had basically stopped shopping in stores and another writer had tipped me off that Smoking Goose Meatery, a charcuterie/butcher shop in Indianapolis, IN with a thriving mail order business, was having a massive online sale. We loaded our fridge with sausages and various artisanal Italian-style meats, and paging through the cookbook American Sfoglino, we discovered we had nearly everything to make “lasagna verde alla bolognese.”

American Sfoglino is the kind of book specifically designed for both professional chefs and Serious Food People (you know, the kind of person who waxes on about the artisanal dried beans from Rancho Gordo and has a lifetime subscription to Saveur). While chef and pasta evangelist Evan Funke (of LA’s Felix Trattoria) is listed as the primary author, it’s likely the secondary author, food and cookbook writer Katie Parla, was actually responsible for the bulk of the text and recipe testing. Conceptually, this makes sense; Funke likely doesn’t have the time (or training) to write a cookbook, and Parla has made a career for herself by writing about the food of Italy, and was a scout of the second season of Master of None, which began with Aziz Ansari’s character Dev Shah living in Modena and learning how to make pasta.

American Sfoglino is an ambitious cookbook and the lasagna verde is its most involved recipe. Funke describes it as “the lasagna that all others aspire (and fail) to be” and the recipe—named for the fact that it uses homemade sheets of pasta made with spinach purée—calls for no fewer than FOUR sub-recipes:

Brodo de carne - a type of clear, fortified Italian broth similar to a consommé, made with meat and vegetables simmered for 24 hours

Ragù della vecchia scuola - a ragu named for the Italian pasta school Funke attended, La Vecchia Scuola

Sfoglia verde agli spinaci - pasta with spinach

Besciamella - the Italian version of béchamel, a white sauce of French origin made from a white roux of butter and flour mixed with milk, salt, and grated nutmeg

The entire process would take three days.

Step one was the brodo.

Cooking the meat and vegetables for literally 24 hours, at the barest of simmers, infused our apartment (and probably a significant portion of the rest of our small apartment building) with the smell of meat.

This stage also revealed that the American Sfoglino cookbook had problems, as the volume measurements were significantly off. As the below Instagram post notes, the brodo recipe says that the final volume will be larger than the amount of liquid you have to add to the pot at the start of cooking. Given that a significant amount of evaporation occurs during this kind of cooking—and that the recipes says to cook the brodo uncovered—it would take an actual, Jesus-level miracle to end up with more liquid than I started with.

The brodo produced a scum that was almost black, and a significant volume of rendered fat. While the scum was thrown away the fat was reserved and saved for future cooking. The same went for the disintegrated vegetables and meat, both of which we saved to make strozzapreti al lesso ripsassato, a dish of strozzapreti pasta (a type of thin, twisted pasta whose name means “priest stranglers”) tossed with the leftover meat, which has been fried in lard and tossed with homemade tomato sauce (passata di pomodoro).

The strained, clarified brodo was a clear broth the color of burnished copper, with a final volume of 4.5 quarts. Given that the cookbook said it would produce nine quarts, and that I had been topping off the liquid pretty consistently throughout the cooking, the cookbook wasn’t even close to correct. This is a huge discrepancy which suggests that not only was the recipe sloppily tested, it might not have been tested at all. It was also problematic because the brodo was destined for the ragu, which only required 2 cups worth. This means that we allocated the rest for tortellini in brodo, and having way less than anticipated could also screw up that meal.

After the brodo came the ragu, which required mortadella, pancetta, prosciutto, beef chuck (we used a brisket), and pork shoulder. The cost of the meat alone was enormous, although this isn’t something either Funke or Parla can be faulted for. It’s not their fault that the pasta school’s recipe calls for pricey meats which are common place (and presumably less expensive) in Bologna.

The ragu cooked for a solid 8 hours or so, at which point we put it in containers to cool.

The last part, beyond making the besciamella (which really isn’t difficult, and not worth picturing), is the making and blanching of the pasta. This was where things really started to deteriorate within the lasagna recipe.

For the spinach to properly incorporate into the pasta dough you need a true puree, free from small, floaty bits of spinach. Without that the pasta will look awful, and I imagine you’ll also experience problems with texture. Parla and Funke’s recipe calls for fresh spinach to be blanched (which helps the spinach keep its vibrant green color), squeezed of excess water (because watery dough would be a disaster), and then mixed with eggs in a food processor. Here’s what it looked like:

This is very clearly not right. The color is off, the texture is off, and it looks foamy.

Here’s what it looks like if you make it in a blender.

This is clearly how it’s supposed to look, and we were able to figure this out in a couple of ways. First, we checked our puree (and its color) against the photos in the book, which clearly demonstrated we had done something wrong by using the food processor. And, in checking the images, we discovered copywriting errors. Not a good sign, folks.

Once we had determined the color and texture was off, we had to figure out how to repair the purée. The blender seemed like the only viable option, but it was risky. For one thing we use a Vitamix, an extremely high powered blender often used in professional kitchens that has such a powerful motor it can actually generate heat. Exposing the egg mixture to heat would be a disaster, as the last thing we wanted to do was to cook the eggs in the purée as the motor is running (which I assure you can happen). Scrambled spinach blender eggs is a bad look.

We decided to use the blender but to intermittently pulse, thus giving us texture and moderating the heat from the motor. This was the correct decision and the end result was obviously better, and illustrates again that the American Sfoglino cookbook wasn’t adequately tested.

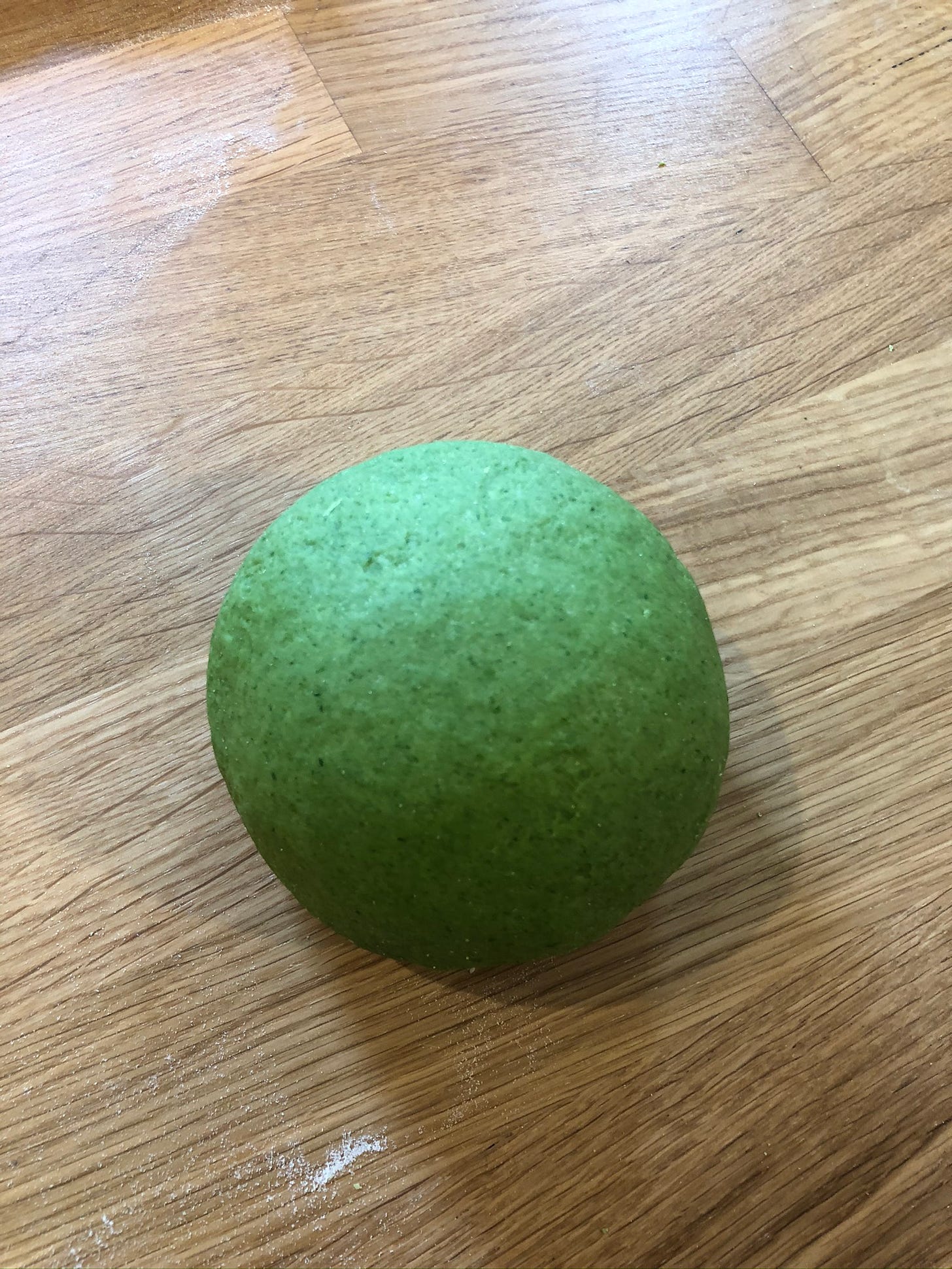

Here’s the dough after the spinach mixture was added to the flour and it was mixed, kneaded, rested, and kneaded again.

Next, the dough was blanched and then layered in the lasagna pan with the besciamella, ragu, and a significant volume of parmigiano-reggiano.

Our pasta was thicker than we would have wanted (we had trouble rolling it out without a traditional rolling pin called a mattarello), but we were still pleased.

And here’s the (quite greasy) end result:

The dish, while flawed, was phenomenal. Unlike Italian-American lasagnas there was no mozzarella or ricotta, and neither was missed. The lasagna, though extraordinarily oily and quite salty, was also incredibly delicious.

So if the lasagna was delicious, what’s your problem with this book?

Recipe testing is a serious task. A poorly designed and tested recipe doesn’t just waste people’s time and money, it destroys the credibility of both the chef whose name is on the cover, and of the writer who was powering their cookbook and their vision. The errors in the American Sfoglino book—problems with yields, copywriting, and cooking procedures—make the book untrustworthy. It makes Evan Funke look like he doesn’t know what he’s doing. And it makes Katie Parla look like an amateur.

But, maybe that’s the problem. Shortly after I began this project Katie Parla (whom Eater profiled in a story titled, “How I Got My Job: Becoming a Go-To Food Authority in Rome” became the center of a controversy in which it was revealed that food writer/author Kristina Gill—who is Black—received effectively zero credit for working on the book Tasting Rome, the book which helped Parla build her reputation as an authority on Italian food. Gill co-wrote the book, but from how Parla portrays both herself, and that work, you’d never even suspect she had assistance.

In response to these allegations Parla posted what was (at least in my eyes) an incredibly inadequate apology on Instagram and a since-deleted post explaining (badly) why Gill didn’t receive credit. She basically passed the buck on the entire debacle, a decision which likely saved her career but also made her look like she was overtly trying to get away with doing something she knew was wrong.

The state of the American Sfoglino cookbook suggests that Parla’s career as a food writer may be a bit of a house of cards. While she was listed as the secondary writer on this book, in the typical fashion for chef-driven cookbooks, Parla was very likely the one actually responsible for writing and testing these recipes. These are her errors, her responsibility. Her failure to provide credit to Kristina Gill in her previous book, combined with the errors in American Sfoglino, suggests that she doesn’t actually know what she’s doing.

So what happens next?

Sadly, the American Sfoglino cookbook will no longer have a place in my home. I don’t have the time or energy to make sure every subsequent recipe actually works, and whatever good will the book may have engendered via its delicious lasagna was squandered. And, sadly, the errors in the text will likely live on. There’s no advantage to the publisher to go through the onerous process of updating the text, and as far as I can tell the book wasn’t a best-seller, so I can’t imagine it will be reprinted, now or in the future. This will likely be yet another chef-driven cookbook forgotten by the industry: alone, poorly tested, and not particularly useful, an embarrassment to its named chef and to the author who inexpertly wrote the book and tested its recipes.

AND, adding insult to injury, the binding glue broke, likely a sign of both poor manufacturing and spiritual decay on behalf of the people who assembled this disappointing volume.

Have thoughts on this story?

Think someone else might enjoy this (or hate it)?

Not already a subscriber? (Seriously, what are you waiting for?)

Thank you for this post! I’m sitting here reading the brodo di carne recipe and completely mind boggled by the fact that 6 quarts of water simmered for 24 hours will yield 9 quarts of brodo! What a joke. I’ve been so fascinated by this book which I just purchased but to now seeing such basic flaws is really unfortunate. Likewise I’ve been studying the wild boar ragu recipe. He calls for 5-6 torn sage leaves and 5 whole juniper berries. That’s a serious amount of sage and big pieces of it at that. Not a single one of which is in the picture and would normally be pretty atypical (at least at that size) in a finished ragu. Then whole juniper berries are usually used for marinades - not frequently tossed into a meat sauce whole so you’d think at a min they’d be ground. The more I read this the more that things all seem quite off! Frustrating. But your parting comment is probably true - this will never get corrected and seeing as how it wasn’t even so easy to find probably says it all…

Thanks again.

I've made Lasagna many a time in my life but I've never heard of anything like this. Wow!